One great universal law runs through the realm of nature. Our Saviour gave it in a sentence: 'First the blade, then the ear, after that the full corn in the ear.'

It is with the desire to show that the same law rules in another of God's creations—The Bible—that this little volume has been prepared.

The Bible has as literally 'grown' as has an oak tree; and probably there is no more likeness between the Bible as we know it to-day and its earliest beginning, than we find between the mighty tree, and the acorn from which it sprang.

The subject is so vast that we have not attempted anything beyond the briefest outline. Our purpose has been merely to give some idea of the origin of the Bible books, up to the measure of our present light upon the subject, and also to show the purpose for which they were written.

But if our readers, by seeing something of the wonder and glory of the Holy Scriptures, are able to catch a glimpse of the Creator's mind behind the whole, our work will not have been in vain.

MILDRED DUFF.

here is only one Book that never grows old.

For thousands of years men have been writing books. Most books are forgotten soon after they are written; a few of the best and wisest are remembered for a time.

But all at last grow old; new discoveries are made; new ideas arise; the old books are out of date; their usefulness is at an end. Students are the only people who still care to read them.

The nations to which the authors of these first books belonged have passed away, the languages in which they were written are 'dead'—that is, they have ceased to be used in daily life in any part of the world.

Broken bits and torn fragments of some of the early books may be seen in the glass cases of museums. Learned men pore over the fragments, and try to piece them together, to find out their meaning once again; but no one else cares much whether they mean anything or not. For the books are dead. They cannot touch the heart of any human being; they have nothing to do with the busy world of living men and women any more.

Now, our Bible was first written in these ancient languages: is it, therefore, to be classed among the 'dead' books of the world?

No, indeed. The fact alone that the Word of God can be read to-day in 412 living languages proves clearly that it is no dead book; and when we remember that last year 5,000,000 new copies of the Bible were sent into the busy working world for men and women by one Society alone, we see how truly 'alive' it must be.

Nations may pass, languages die, the whole world may change, yet the Bible will live on. Why is this?

Because in the Bible alone, of all the books seen on this earth, there is found a message for every man, woman, or child who has ever lived or will live while the world lasts:

It is the Message of God's Salvation through His Son Jesus Christ.

The message is for all; for the cleverest white man, the most ignorant savage; for the black man of Africa, the yellow man of China, the tawny little man who lives among the icefields of the Arctic Circle.

It does not matter who the person is, nor where he lives; a living force exists in the Bible that will help every human being who acts upon its words to become one of God's true sons and soldiers. No human wisdom can explain this.

The Bible tells us about Christ. Before Christ came all teaching led up to Him. He is the only safe Guide for our daily life. Through His death alone we have hope for the future. From the first page to the last the Bible speaks of Christ. This is the secret of its wondrous power.

'These are the words which I spake unto you, while I was yet with you, that all things must be fulfilled, which were written in the law of Moses, and in the prophets, and in the Psalms, concerning Me.' (Luke xxiv. 44.)

Although we speak of the Bible as one Book, because it tells one world-wide story, yet this one Book is made up of many books—of a whole library of books in fact.

Go into a library, look at the well-stocked shelves. Here is a volume of history, here a book of beautiful poetry, here a life of a great and noble warrior. This book was written only last year, this one appeared many years before you were born.

Just so is it with the books of the Bible.

For more than a thousand years God was calling the best and wisest men of the Jewish nation to write for His Book. Some of the authors were rich and learned; many were humble and poor. Kings wrote for it; a shepherd-boy; a captive lad who had been carried away as a slave into a strange land; a great leader; a humble fruit-gatherer; a hated tax-collector; a tent-maker; many poor fishermen. God found work for them all.

There are sixty-six books in the Bible, written by at least forty different authors. Books on history; collections of sacred songs; lives of good men and women; stirring appeals to the sinful. God chose the men best fitted to write each part. He called them to His work; He spoke to their hearts; He put His Spirit into their minds.

In these days those who read God's Word often forget what old, old writings the first books in the Bible are, and how everything has changed since they were written.

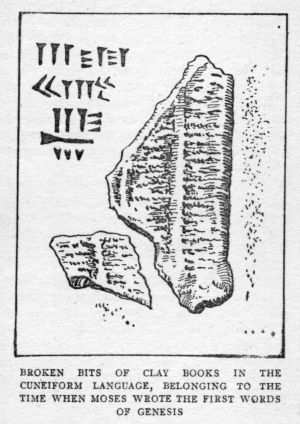

Seeing the words so clearly printed on fine white paper, readers do not stop to think that they have come down to us from the days when the greatest nations in the world wrote their best books on lumps of clay, or on rough, brittle paper made from brown reeds.

So these Bible readers grow impatient, and because they cannot understand everything all at once, some are even foolish enough to give up reading the Old Testament altogether.

But the things that are hard to understand are only hard because we are still so ignorant. Whenever any new discovery about the ancient times has been made it has always shown us how exactly true the Bible is.

Some years ago, just at the time when the doubts and carpings were at their worst, when those people who did not trust God even declared that many of the cities and kings mentioned in the Old Testament had never existed at all, a wonderful thing happened. God allowed the old cities themselves to be brought to light once more.

Deep under the earth they were found, with their beautiful palaces, libraries full of books, and long picture-galleries, lined from end to end with stone and marble slabs, on which were cut portraits of the very kings whose existence the people were beginning to doubt! This is how it happened.

'The Bible does not describe things as they really were,' said some people. 'In Old Testament times, for instance, the nations were very rough and ignorant; as for Moses—who is supposed to have written the first books of the Bible—it is most doubtful whether he ever learned to read and write at all.'

'But Moses was brought up in Egypt, and the Egyptians were very learned; the Bible says so,' answered others.

'The man who wrote those words in the Bible may have made a mistake. It is true that the ruins of old Egyptian temples and palaces are covered with strange figures and signs; but who can say now whether they mean anything or not?'

Those who trusted in God's Word could not answer these questions; but just at this time God allowed the first great discovery to be made; for the moment had at last come when all thoughtful men and women needed to be able to settle these questions for themselves.

In the year 1799 a French officer who was in Egypt with Napoleon's army discovered the Rosetta Stone.

You may see this stone in the British Museum. It is a great block of black marble. On the smooth side, cut deeply in the stone, are a number of lines of ancient writing. Many stones covered with ancient writing had been found before, but this one is different from all the rest.

The lines at the top of the stone are in the strange old Egyptian picture-writing, which learned men have agreed to call 'Hieroglyphic'; that is, 'writing in pictures.' This was a very special kind of writing in ancient Egypt, and generally kept for important occasions. The lines in the middle give the same words, but in the ordinary handwriting used for correspondence in ancient Egypt; and last of all is found a translation of the Egyptian words written in ancient Greek.

This old kind of Greek is not spoken in daily life by any people to-day, but many learned men can read and write it with ease; so that, you see, by the help of the Greek translation, the Rosetta Stone became a key for discovering the meaning of both kinds of ancient Egyptian letters. Thus, by the help of the Rosetta Stone, and after years of patient labour, the long-dead language could be read once more.

Egypt—the land into which Joseph was sold, where the Israelites became a nation, and Moses was born and educated! How great a joy to read the words carved on temple walls, or in palace halls; and to find with each word read how exactly the Egypt of ancient days is described in the Bible!

The dress the people wore, the food they ate, the way they spoke to their kings, the description of their funerals, the very name of their famous river, and the words they used to describe the plants, insects, and cattle of Egypt—all these are found in the Bible and are proofs of the care with which Moses wrote of the land of his birth.

But other nations besides the Egyptians are mentioned in the Bible; and about them also grave doubts arose. Almost all the Old Testament prophets cried out against the wickedness of Assyria and Babylon, and foretold the awful punishment which God would bring upon them for their pride and cruelty, unless they repented.

They did not repent; destruction came upon them; their very names were forgotten, and their cities as utterly lost to the world as though they had never existed.

'Nineveh, Babylon? There were such cities once, perhaps; but as for the kings of whom the Bible speaks—Sennacherib, who came up against Jerusalem, and was driven back through the prayers of God's servants, Isaiah and King Hezekiah (2 Kings xviii. 19); Nebuchadnezzar, who carried Daniel away into Babylon; Ahasuerus, who reigned "from India even unto Ethiopia" (Esther)—well, if they ever lived at all, they were certainly not the kind of kings spoken of in the Old Testament. But it all happened so long ago that we cannot expect to understand much about it now.'

So the questioners settled the matter in their own minds; but God had the answer to their questions all ready for them.

He put into the hearts of some brave men the idea of going out to the desolate plains, 'empty and void, and waste' (Nahum ii. 10), the plains that had once been the rich empires of Assyria and Babylon, and there to search patiently for some trace of the splendid cities of old.

Very wonderful is the story of how these searchers found them.

Nineveh had been lying buried under huge mounds of rubbish for more than two thousand years. Now, just at the time when her testimony was needed, the ruined halls of her majestic palaces were once more brought to the light of day.

What had been the names of these grim kings of old, whose stern-faced figures were sculptured on the walls? Could any among them be the fierce Assyrian kings mentioned in the Bible?

If only the strange wedge-shaped letters that covered every vacant space on the stone slabs could be read, what a message from the past they would reveal.

Once again clever men set to work and persevered until the strange letters were deciphered, and the palace-walls gave up their secrets. Here was King Sennacherib; here Tiglath-pileser (2 Kings xv. 29); here Esarhaddon (2 Kings xix. 37). Oh, how wonderful to look at the old-time portraits which had been drawn from the men themselves!

'Well, although the Egyptians and Assyrians prove to have been great nations in the time of Moses, they had no communication with each other except in war time; they spoke different languages, wrote in altogether different styles, and had very different ideas about everything. Nations kept to themselves in those days. What the Bible says of their intercourse must be wrong.'

This all the clever people were quite sure about, but once again God showed them their mistake.

Twenty-five years ago an Egyptian peasant woman was walking among the ruins of an ancient Egyptian city—a city built before the time of Moses. Bright yellow sand had drifted over the broken columns and painted pavements of what had once been the palace of a great king. But the peasant woman did not care for that. Was there anything hidden in the sand that she could sell? This was all her thought.

Suddenly her foot struck against something hard in the sand. She looked down. Could it be a stone?

No, it was not a stone, but a queer oblong lump, or tablet of clay, hardened into a brick, and covered with strange marks that looked like writing. She wondered at it, for with all her findings in the ruins she had never come upon anything like this before.

She showed the tablet to her friends, and they dug down deep in the sand, and found whole sackfuls of baked clay tablets. But when the dealer in curiosities saw the lumps of baked clay he shook his head, and would give very little money for them.

After a while some of the bricks were taken to Paris and London.

'These tablets could not have been found in Egypt,' decided the learned professors; 'they are either imitations, or they were found somewhere else. These are clay letters, and must have been written in Assyria or Babylonia. No Egyptian could have understood a word of them.'

Yet the tablets had been found in Egypt, and had been read by the king of Egypt's scribes, for the peasant woman, had all unknowingly discovered what remained of the Foreign Office belonging to the old Egyptian nation, and thus we see that the Egyptians of Moses' time could read and write foreign languages as easily as we can to-day read and write French or German!

od always chooses the right kind of people to do His work. Not only so, He always gives to those whom He chooses just the sort of life which will best prepare them for the work He will one day call them to do.

That is why God put it into the heart of Pharaoh's daughter to bring up Moses as her own son in the Egyptian palace.

The most important part of Moses' training was that his heart should be right with God, and therefore he was allowed to remain with his Hebrew parents during his early years. There he learned to love and serve the one true God. Without that knowledge no education can make a man or woman fit to be a blessing to the world.

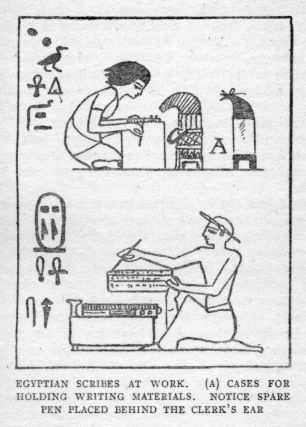

But after this God gave him another training. The man who should be called to write the first words of God's Book would need a very special education. Most likely some of the Children of Israel could read and write, for we know there were plenty of books and good schools in Moses' time, but they certainly did not make such good scholars as the Egyptians.

'And the child grew and she (his mother) brought him unto Pharaoh's daughter, and he became her son.' (Exodus ii. 10.)

In those few words the Bible shows us the Egyptian side of Moses' education.

And a very thorough education it must have been, for the Egyptians were the most highly cultured people in the world in those days, and we know that 'Moses was learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians.' (Acts vii. 22.)

The Egypt of Moses' time was very different from the Egypt of to-day. Among all the great nations it held the first place; for the people of Egypt were more clever, and rich; their gardens more beautiful, their cornfields and orchards more fruitful than those of the dwellers in any other land.

Again, of all the peoples in the world the Egyptians were looked upon at that time as the most religious. From one end to another the land was full of temples, many of them so huge in size, and so magnificent with carvings and paintings, that even their poor ruins—the great columns shattered or fallen, the enormous walls tottering and broken—are still the wonder of the world.

Every great city had its schools and colleges. Clever men devoted their whole lives to teaching in these colleges and to writing learned books, just as they do in the cities of Europe and America to-day. These men were called 'scribes,' that is, 'writers.' Moses, a boy brought up in the royal palace, would have the best and most learned scribes for his teachers.

A fragment of an old Egyptian book describing the duties of a lad in the scribes' school has been found. It tells how the schoolmaster wakes the boys very early in the morning. 'The books are already in the hands of thy companions,' he cries; 'put on thy garments, call for thy sandals.'

If the lad does not make haste he is severely punished; if he is not attentive in school the master speaks to him very seriously indeed. 'Let thy mouth read the book in thy hand, and take advice from those who know more than thou dost!'

He has to write many copies, and as he gets he learns to compose business letters to his master; before he is fourteen he is most likely a clerk in a government office, and must continue his studies at the same time.

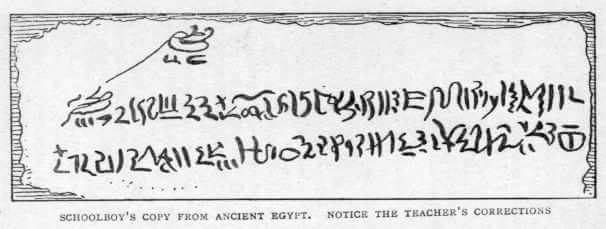

The letters and copies of a schoolboy who lived three thousand years ago have been discovered. How many bad marks did his teacher give him, do you think, when he had to correct that carelessly written capital?

So great a respect had the Egyptians for writing that they used to say, 'The great god Thoth invented letters; no human being could have given anything so wonderful and useful to the world.'

Arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, drawing, an Egyptian lad was supposed to study all these, and as we have seen, those lads who were trained for work in the Foreign Office had to learn other languages as well; they had also to read and write 'cuneiform'—the name given to the strange wedge-shaped letters of Assyria and Babylonia.

All the letters from the people of Canaan to the Egyptian king and his Foreign Office were written in cuneiform.

Chinese is supposed to be the most difficult language to learn in our day; but the ancient cuneiform was certainly quite as complicated as Chinese. The cuneiform had no real alphabet, only 'signs.' There were five hundred simple signs, and nearly as many compound signs, so that the student had to begin with a thousand different signs to memorize. Yes, boys had their troubles even in those days.

Now, as Moses grew older and learned more, he must often have felt very thoughtful and sad. So many books, so many ideas, so many stories of cruel gods and evil spirits—where was the truth to be found? No one seemed to remember the One True God, the God of his fathers, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Very likely a Babylonian book written in cuneiform, and pretending to describe the Creation of the world, and the story of the Ark and the great Flood found its way into Egypt. Many copies of this book existed in Moses' day; part of a later copy was found a short time ago in the ruins of the library of a great Assyrian king, and is now to be seen in the British Museum. A strange book it is. The words were not written, remember, but pricked down on a large flat tablet of clay.

If Moses read such a book as this, it must have troubled and puzzled him very much. For it is a heathen book, in which the beautiful clear story of the Creation of the world is all darkened and spoilt. The Babylonian who wrote the book, and the Assyrians who copied it, were all descended from Noah, and therefore some dim remembrance of God's dealings with the world still lingered in their hearts; but as the time passed they had grown farther from the truth. That is why the oldest copies of these books are always the best; the heathen had not had time to separate themselves so completely from God.

'In the old, old days,' they said, 'there were not so many gods as there are now'; and some of the most learned heathen even believed that in the beginning there was but one God. 'Afterwards many others sprang up,' they declared.

'In the beginning God created the Heaven and the earth.' (Genesis i. 1.) Oh, how far the nations had wandered already from the greatest, deepest truth which the world can know! How sad to think that horrible nightmare stories of evil spirits and cruel gods should have come between men's souls and the loving Father and Creator of all!

Yes; it was time, indeed, that the first words of the Bible should be written, and that a stream of pure truth should begin to flow through the world.

But Moses had much to do for God before he could write one word of his part of the Bible.

We know how his life of learning and splendour came to a sudden end; he fled from Egypt, and became a shepherd in the land of Midian; and there in Midian God called him to the great work of leading the Children of Israel out of Egypt towards the Promised Land.

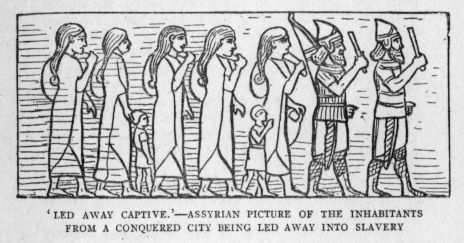

Terrible troubles had come upon God's people in the land of Goshen.[1] For the most selfish and cruel Pharaoh who ever reigned over Egypt had determined to treat the people who had come to live in Egypt, at the invitation of a former Pharaoh, just as though they were captives taken in battle.

Many of the old ruins in Egypt are covered with writings describing his cruelties. He killed all who rebelled against him, and condemned whole nations to wear out their lives by working for him in the gold mines, or granite quarries, or by making endless stores of bricks; he cared for no man's life if only he could be called the richest king in the world.

'And they built for Pharaoh treasure cities, Pithom and Raamses,' (Exodus i. 11) that is, store-cities. In Egypt many store-cities were needed because corn was more plentiful there than in any other country.

'Pithom—where was Pithom?' So people were asking a few years ago, and because there was no answer to that question they began to doubt. Had there ever been such a city?

But in the year 1884 the earth gave up another of its secrets—the ruins of Pithom were found, buried deep in the dust; and the remains of great store-houses built of rough bricks, mixed with chopped straw (Exodus v.) and stamped with the name of the cruel Pharaoh (Ramesis the Second) were laid bare once more.[2]

What a pity some readers had not waited a little longer before doubting the truth of the Bible!

'And the Lord said unto Moses, Write thou these words.' (Exodus xxxiv. 27.) So it was at last that God called Moses to begin the great work of writing the Bible, just as He had called him to lead the people out of Egypt; just as by His Spirit He calls men and women to do His work to-day.

How did Moses write the first words of the Bible? What kind of letters and what language did he use?

These are great questions. We know at least that he could have his choice between two or three different kinds of letters and materials.

Perhaps he wrote the first words of the Bible on rolls of papyrus paper with a soft reed pen, in the manner of the Egyptian scribes.

Hundreds of these rolls have been found in Egypt: poems, histories, novels, hymns to the Egyptian gods; and some of these writings are at least as old as the time of Moses. The Egyptian climate is so fine and dry, and the Egyptians stored the rolls so carefully in the tombs of their kings, that the fragile papyrus—that is, reed-paper—has not rotted away, as would have been the case in any other country.

Certainly in after years the Jews used the same shaped books as the Egyptians. Indeed, the Jews' Bible—that is, the Old Testament—was still called 'a roll of a book' in the days of Jeremiah. (Jeremiah xxxvi. 2.)

Or perhaps Moses wrote on tablets of clay like those used by the great empires of Babylon and Assyria, and by the people of Canaan. Clay was cheap enough; all one had to do was to mould moist clay into a smooth tablet, and then to prick words on it with a metal pen. The prophet Jeremiah mentions this kind of book also. (Jeremiah xvii. 1.)

Most likely, however, Moses wrote on parchment made from the skins of sheep and goats. The Children of Israel kept large flocks, and could supply him with as many skins as he wanted.

And in what language did he write?

Perhaps even the very first words were written in Hebrew; we know that in later times the prophets and historians of the Jews wrote in Hebrew.

But we must remember that languages alter as years pass on. The Hebrew of Moses' time could only have been an ancient kind of Hebrew, very different from the Hebrew of to-day. Does this surprise you? Why, you and I could hardly read one word of the English written in England even a thousand years ago!

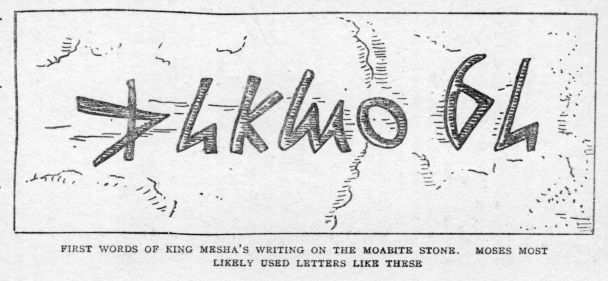

About the middle of the last century a German missionary found a large carved stone in that part of Palestine which used to be called Moab. This wonderful stone, which is black and shaped something like a tombstone, is covered with writing. It is called 'The Moabite Stone,' and was set up by Mesha, king of Moab. (2 Kings iii. 4.) The writing on it is neither Egyptian nor cuneiform, but a very ancient kind of Hebrew.

Of course, this does not take us back actually to the days of Moses, but still it is so old that Moses may well have used the same kind of writing.

We have seen that most nations in those old times had their books, and we know that each nation had always one book that it valued more than the rest. This was the book that told the people about their religion, and the gods in whom they believed.

In most of these books some grains of truth were found. All the nations of the world are but one great family, you know, and even the most ignorant people were not without some knowledge.

The heathen nations of Moses' time therefore remembered dimly some of God's dealings with the world; they were so blinded by their heathen worship, that no atom of fresh light could reach them, and little by little they drifted further into the darkness.

But, though tiny fragments of truth are to be found in their books, not one word is to be traced in any book of the most precious truth of all until God revealed it to His servant Moses.

This makes our Bible so wonderful and different from all other books: it is a revelation—that is, something which comes to us from God and which we could never have known without His help.

From first to last the Bible is written to teach us about Christ. Throughout the whole of the Old Testament Christ is referred to as the coming Saviour, or Messiah, which you know, is the Hebrew word for Christ.

Christ is to bruise the serpent's head. (Genesis iii. 15.) In Him all the nations of the earth are to be blessed. (Genesis xxii. 18.) He is the Star that shall come out of Jacob. (Numbers xxiv. 17.) When the Lamb of the Passover was killed, and the people taught they could only escape from death through the sprinkled blood, this was a type or picture of Salvation through the Blood of Jesus.

When at last the Saviour came, the Jews rejected Him and would not accept Him as the Messiah. Then He said to them: 'Had ye believed Moses, ye would have believed Me: for he wrote of Me.' (John v. 46.)

[1] The Egyptians spelt 'Goshen' 'Kosem.' An old writing says, 'The country is not cultivated, but left as a pasture for cattle because of the stranger.'

[2] Some of these bricks are in the British Museum.

e now begin to understand a little of the very beginning of God's Book—of the times in which it was written, the materials used by its first author, and the different kinds of writing from which he had to choose; but we must go a step farther.

How much did Moses know about the history of his forefathers, Abraham and Jacob, and of all the old nations and kings mentioned in Genesis, before God called him to the great work of writing his part of the Bible?

We believe that he knew a great deal about them all.

Most thoughtful young people like to read right through their Bibles, and perhaps you have been perplexed to find that many parts of the Old Testament are both puzzling and dry. Of what use, then, can these chapters be? you have perhaps asked yourself. Is it not all God's Book?

But you must not let this trouble you. Every passage, every verse has its special place and object. Not a line of God's Book could be taken away without serious loss to the whole.

'What, all those long lists of the queer names of people we never hear of again?' asks some one. 'Why, I dread those chapters. I once had to read Genesis x. aloud, and I shall never forget it!'

Those who feel like this will be surprised to know that many of the most learned men of our own days are giving much time and thought to the careful and patient study of this very list of names; and the more carefully they study it, the fuller and wider does the subject become.

'Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar.' (Genesis x. 10.) The ruins of all these great cities and kingdoms have now been found. They were old before Moses was born; indeed, they were so old that their names were only to be found in ancient books; even the very language spoken by some of these nations had been forgotten by all save the learned scribes of Babylonia and Assyria.

And yet we find these names accurately given in Genesis; had they been missing from its pages, the Bible would give us no true idea of the beginnings of history. Remember this when next you are tempted to feel impatient at the awkward syllables.

Again, in Genesis xiv. we read the names of the kings who governed nine nations in the time of Abraham, and of how they fought together 'four kings with five' (verse 9) three hundred years before Moses was born.

Until a very few years ago the Bible was the only Book that told us about these ancient kings and kingdoms.

And people said, 'The man who wrote that chapter did not really know anything; he just collected a pack of old stories that had been repeated over and over again with so many exaggerations and alterations that at last there was scarcely a word of truth left in them.'

Since this foolish conclusion was arrived at many new discoveries have been made, the broken fragments of old tablets have been pieced together and read, and the names of all the nine kings brought to light once more.

Certain it is that Moses, with the help of the writings which we now know must have existed in his time, would have but little difficulty in writing those parts of Genesis which tell us the history of some of the most ancient nations of the world. For when God gives a man some work to do, He always helps him to do it. To those who really trust Him, and have patience to work on, the help they need always comes, the difficult path is made smooth. This has been the experience of God's servants in all times.

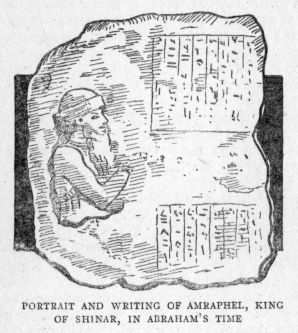

Many letters and books belonging to the reign of 'Amraphel[1] king of Shinar' (Genesis xiv. 1) have lately been found. He was one of the wisest heathen kings who ever lived, and the writings of his times are very interesting, because they bring us quite back to the days of Abraham.

Amraphel kept written records describing the splendid temples he built, and a great embankment which he made to keep the river Tigris from flooding his people's cornfields; but the wisest thing he did was to collect and write out a long list of all the laws by which he governed the land of Shinar. Thus he worked in very much the same kind of way for Shinar that our own King Alfred did, thousands of years later, for England.

This list of laws was found in 1901. They are engraved on a great block of black marble, and are so numerous that they would fill pages of our Bible.

They are wise and just as far as they go. There is a great deal about buying and selling in them, and the lawful way of conducting different kinds of business; but they are wholly different from those wonderful Commandments which God gave to the Children of Israel three hundred years later.

For Shinar's laws were the heathen laws of a heathen king; in them there is no word of God; no word even of the heathen gods in which Amraphel believed.

'Thou shalt love the Lord thy God ... and thy neighbour as thyself.' (Luke x. 27.) In these words Jesus Christ gives to us the true meaning of the Commandments which Moses wrote down in our Bible.

Again, until quite lately many people were certain that there could never have been a king like Melchizedek, the king of Salem, who came and blessed Abraham, and of whom we read in Genesis xiv. and also in Hebrews vii.

But among the letters found in the Foreign Office of the king of Egypt, is one from the king of Salem. Not from Melchizedek, but from another king of Salem, who describes himself in these words: 'I was set in my place neither by father nor mother, but by the Mighty King'—meaning 'by God.' Read what is said about Melchizedek in Hebrews vii. These words show us that all the kings of Salem believed that they owed everything to God. This is why Abraham honoured Melchizedek so highly.

'Salem—that is, peace. 'Jeru-salem' means city of peace. So, as we see from these ancient letters, Jerusalem was called the city of peace even in the days of Abraham.

All these old records and many more Moses must surely have seen; the cities of Canaan were as full of books as were those of Egypt and Babylonia, for the name 'Kirjath-sepher' (Joshua xv. 15) means 'City of Books.'

Thus, as year by year new discoveries are made, we realize more clearly the kind of preparation which Moses had for his great work, and the sources from which he gathered much of his information. Yet no single word of the Bible is copied from the heathen writings.

No; just as a man who decides to give his whole life to God to-day uses, in the Lord's service, the knowledge he gained before he was converted; so, after God called Moses to his great work, all the learning and wide knowledge he had gathered during his life were dedicated to the service of God, and used by His Holy Spirit.

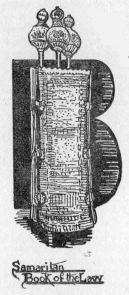

We do not know—we are nowhere told—whether Moses wrote every word of the 'Books of the Law.' The Jews believed that every letter, every tiniest dot was his. It may well have been so, as we have seen.

But, again, he may very likely have had helpers and editors; that is, people who arranged and copied his original writings.

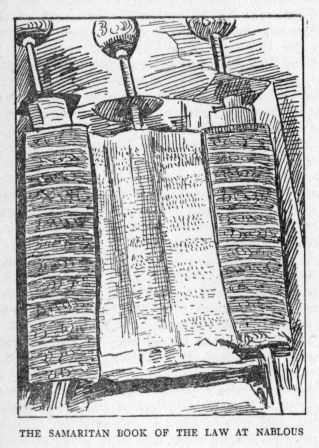

But the Children of Israel always called the first five books of the Bible 'The Torah'; that is, 'The Law'; and they looked upon these as their most precious possession, something quite above and apart from every other writing—Jehovah's direct words and commandments to His people.

At last the life-work of Moses was done, and Joshua took his place, called by God to lead the people forward. But the new leader found himself at once in a very different position. When Moses brought the Children of Israel out of Egypt they were without a Bible.

But in Joshua's days the light had begun to shine, the river of the knowledge of God to flow, and God was able, therefore, to say to His servant Joshua:

'This book of the law shall not depart out of thy mouth; but thou shall meditate therein day and night, that thou mayest observe to do according to all that is written therein: for then thou shall make thy way prosperous, and then thou shall have good success.' (Joshua i. 8.)

We are not told who was called by God to write the Book of Joshua; we think that Joshua wrote at least a part of it himself, but we all know that it describes how the Israelites came at last into the Promised Land, and drove out the wicked idol-worshippers.

Buried deep in the earth the remains of many old Canaanite cities have been found.

Those of Lachish, the great Amorite city, are specially interesting. We know how the Children of Israel dreaded the Amorite cities. 'Great and walled up to Heaven' (Deuteronomy i. 28), as the people said. Yet, in spite of their great strength, Joshua took them one by one, overthrew them, and afterwards built the Jewish towns upon their ruins. This was the custom of conquerors with all these ancient cities, as the excavators find to-day.

Now, in the remains of Lachish we can see its whole history. Three distinct cities have been found, one below the other.

Deepest down of all, full sixty feet underground, are the enormous walls of the Amorite city; great masses of rough brick forming huge walls at least twenty-eight feet wide. No wonder the Children of Israel, felt doubtful of victory!

Above the Amorite walls are the scattered fragments of rough mud-huts and cattle shelters. The Israelites had no time to build anything better until Canaan was conquered.

Above these again stand the ruined walls of a later Jewish city, Lachish, as it was in the days of Solomon and the Jewish kings.

A fair city it must have been, built of white stone, the capitals of some of the columns carved to resemble a ram's horn, perhaps to remind the people of the horns of the altar in the Tabernacle. But the walls of the Jewish Lachish have none of the massive strength of the ancient Amorite city.

Had we space we might pause over many of the other ancient Canaanitish cities, for the subject is of absorbing interest, but perhaps we may return to it in a later volume. Joshua, like all God's true servants past and present, made full use of the precious Book, and, 'There was not a word of all that Moses commanded, which Joshua read not before all the congregation of Israel, with the women, and the little ones, and the strangers.' (Joshua viii. 35.)

Before he died he spoke to the people very sorrowfully about their sins. Many of them, in spite of God's commandments and His favour and love, had begun to serve the false gods of Canaan. The people repented at the old leader's earnest words, and they cried, 'The Lord our God will we serve, and His voice will we obey.' (Joshua xxiv. 24.) Joshua made them promise to be steadfast. 'And Joshua wrote these words in the Book of the Law of God.' (Verse 26.) From this we see that Joshua wrote a part, at least, of the Book that is called by his name.

People have often thought it strange that the Children of Israel should again and again break God's clear command, 'Thou shall have no other gods before Me.' (Exodus xx. 3.) How could they have been so foolish as to care for false gods when the living God had done so much for them?

It is the old story. A man who has once given way to drunkenness is not safe unless he puts strong drink out of his life for ever. If he even touches it he is liable to fall back again into its power. So it was with the Children of Israel. The worship of false gods had been the terrible sin of their wilderness wanderings, and now to serve the gods of Canaan became their strongest temptation.

The temples were so strange, so beautiful, the gods themselves so mysterious, and then all was so easy, so pleasant! No stern self-denial was needed; there were no difficult laws to keep; no holiness was asked for. Drinking, feasting, and all kinds of self-indulgence were part of the worship of Baal, and those who served Ashtaroth, the goddess of beauty, might spend their whole lives in wicked and degrading pleasures.

The backsliders of Israel found it only too easy to give up the struggle for right, and to sink down into the horrible wickedness of the heathen tribes around them.

Many people to-day are asking how a God of love and mercy could bid the Israelites utterly to destroy the cities of Canaan, and to kill their inhabitants, but the more we discover of these ancient tribes, the more hopelessly depraved do we find them to have been. For centuries God had been waiting in patience; the warning He had given to them through Sodom's swift destruction had been unheeded; now at last the cup of their iniquity was full (Genesis xv. 16) and the Israelites were to be His means of ridding the world of this plague spot.

In the Book of Judges we see how each time His people disobeyed His command and copied the sins they were called to sweep away, God punished them by letting their merciless neighbours rule over them, till they loathed the bondage and turned once more to the living God.

Had Israel absorbed the vices of these nations instead of destroying them, try to think what the world would have lost! The one channel through which God was giving His Book to man would have become so choked and polluted with vice that in its turn it also would have become a source of infection and not of health.

[1] This king's name is also spelt Hammurabi.

hus little by little the Book of God grew, and the people He had chosen to be its guardians took their place among the nations.

A small place it was from one point of view! A narrow strip of land, but unique in its position as one of the highways of the world, on which a few tribes were banded together. All around great empires watched them with eager eyes; the powerful kings of Assyria, Egypt, and Babylonia, the learned Greeks, and, in later times, the warlike Romans.

How small and unimportant the Israelites appeared to the world then! Yet we know that in reality they were greater than any people the world had ever seen. God's words have been fulfilled; through the Children of Israel all the nations of the world are blessed.

The old empires have crumbled into dust; the great conquerors of ancient days are forgotten; few people to-day remember the names of the wise men of Greece and Rome, but our lives and thoughts are daily influenced by the thoughts, words, and deeds of the Jews of old. Abraham, Jacob, Moses, Samuel, David, Elijah—their very names are nearer and dearer to us than those of the heroes of our own land.

When Queen Victoria was asked the secret of England's greatness, she held up a Bible. Their Sacred Book was all that the Jews possessed. Their whole greatness was wrapped up in it. As the heathen truly said, they were 'The People of the Book.'

And now let us glance at the history books of the Bible. The first and second Books of Samuel have been put together from several other records. Most likely Samuel himself did part of the work. In Shiloh, where he was educated, the old documents were kept, and Samuel, the gifted lad, who so early gave his heart to God, was in every way fitted to write the story of the Lord's chosen people during his own life-time.

The Bible mentions several other histories that were written in these days besides those which we know. 'Now the acts of David the king, first and last, behold, they are written in the book of Samuel the seer, and in the book of Nathan the prophet, and in the book of Gad the seer.' (These last have disappeared.) (1 Chronicles xxix. 29.)

Stores of books were being gathered. When, for instance, Saul was chosen king, Samuel 'wrote in a book and laid it up before the Lord.' (1 Samuel x. 25.) These books were most likely written on a rough kind of parchment, made from the skins of goats, sewn together, and rolled up into thick rolls.

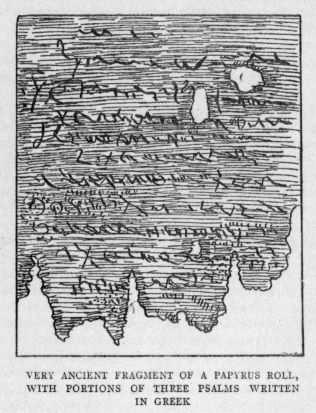

The Books of Samuel are very precious to us, for in them we read nearly all we know of the history of David the shepherd-king. Some of David's own writings are found in these books, but for most of them we have to turn to the Book of the Psalms, which was the manual of the Temple choir, and became the national collection of sacred poems. These Psalms were composed by different authors, and at different times, chiefly for use in the Temple, but the collection was founded by David, and he contributed many of its most beautiful hymns.

David's boyhood was spent among the rugged hills and valleys of Bethlehem. As we read his Psalms we feel that the writer has passed long hours alone with God, and the beautiful things which God has made.

Let us watch him for a moment. It is evening, and the young lad is alone on the hills, keeping his father's sheep The sun is sinking, and all the earth is bathed in golden light. Even the sullen surface of the Dead Sea reflects the glory, and the hills of Moab glow as though on fire.

'God is the Creator of all this beauty,' thinks David. 'Yes, bright as is that golden sky, His glory is above the heavens.' (Psalm viii. 1.)

Now the sun has quite gone; night's dark curtain draws across the world, the rosy glow fades from the hills. One by one the great white stars shine out, and presently the moon rises. The young lad raises his face, and gazes upward. 'When I consider Thy heavens, the work of Thy fingers, the moon and the stars, which Thou hast ordained' (Psalm viii. 3) he murmurs; 'how great is this mighty God, how far beyond all the thoughts and ways of men! What is man, that Thou art mindful of him?' (Verse 4.)

But God loves us even though we are lower than the angels. He has crowned us with glory and honour. He has given all His beautiful world, and all the wonderful things He has made, into our hands. 'O Lord (verse 4) our Lord, how excellent is Thy name in all the earth.' (Verse 9.)

In Psalm xxix. David gives a word picture of a thunderstorm. He describes the furious blast, the crashing thunder, the vivid lightning. Many times as a young lad he had watched the black storm-clouds gather over the hills and valleys of Bethlehem. He had no fear of the tempest. God's voice was in the wind; God's voice divided the lightning-flashes; God's voice shook the wilderness. Yes, God would make His people strong, even as the storm was strong.

And when the storm had passed, and the sun shone out once more over the quiet hills, how clearly the words rose in David's mind, 'The Lord will bless His people with peace!' (Verse 11.)

Solomon, David's son, was the wisest king of ancient times. He wrote many books, but only small fragments of them are found in the Bible; a few Psalms, Solomon's Song, and a collection Proverbs.

For much of Solomon's wisdom was of the earthly sort. He stood first among all the learned men of his day. He would now be called a 'scientific' man. But all science which is limited to mere human wisdom grows quickly out of date. The cleverest men of to-day will be thought very ignorant in a few years.

Whereas David's writings live. His love for God, and his faith in God, made him able to write those words of trust and hope and praise which are as sweet and fresh to-day as when they were written, and which go right home to our hearts.

How many cold hearts have not David's psalms warmed into life, how many wounded spirits have they not comforted! There is not a grief or anxiety in our lives to-day that could not be met and softened by the words of the Jewish writer of long ago. Yes, the work done for God and inspired by His Spirit never grows old.

And now, as we open the books of the kings, the great empires of the days of old, of Assyria, Babylonia, Egypt, Persia, seem to start into vivid life once more.

How strong they were—how terrible! What defence had the little kingdom of Judah against such overwhelming power, such mighty armies, such merciless rulers?

She had the best defence of all—God's holy promises chronicled in His Book. While her people loved and served their God they would be safe.

But, alas! they soon forgot to read and obey His Book, and neither loved nor served Him any more. Then came sorrow and trouble exactly as Moses had foretold. Cities were sacked, and many hundreds of people led away into slavery; yet, until the days of Hezekiah, no one tried to understand the reason for all this.

King Hezekiah understood and trembled; he prayed earnestly that God would pardon the nation's sin, and when the Book of the Law was lying forgotten in the Temple he had it brought out and read before him. (2 Chronicles xxxiv. 14-18.)

Under his direction the Proverbs of Solomon were collected and copied (Proverbs xxv. i), and the Psalms of David sung in the Temple once again.

The wonderful story of the King of Assyria's campaign against Jerusalem, followed shortly after by the defence of the Holy City by God Himself in answer to Hezekiah's prayer, can be read at length in the story of 'Hezekiah the King.'[1]

Although Sennacherib of Assyria was one of the mightiest rulers the world has ever seen, he was utterly discomfited when he set his power against the will of God.

The Books of Kings and Chronicles give us, as it were, the history of a nation from God's point of view.

The writers' names are not even known. But in these Books we are shown clearly that God rules over the nations, and is working His purpose out through His chosen instruments, year by year. It is in vain for a man to strive against God, or for a nation to hope for prosperity while it forsakes the law of the Lord.

No other history has ever attempted to show us the deep truths and perfect order which lie behind apparent confusion in the story of a nation.

With the History Books of the Bible, the Books of the Prophets are closely interwoven. Throughout Kings and Chronicles we catch many glimpses of the prophets and of their noble efforts to keep alive God's words in the hearts of the people; but in the writings of the prophets themselves we may read the actual messages which God's messengers proclaimed in order to stir up their hearers in times of national distress or heart-backsliding.

God's indignation against hypocrites and oppressors is declared in words that cannot be passed over; but ever as the clouds of trouble gather more thickly over His people is the hope of a coming Saviour more clearly put before them.

For a real understanding of the Prophets' Books it is necessary to know something of the circumstances under which each man lived and wrote. Amos and Hosea, for instance, warned their people of the approach of Sargon of Assyria unless they repented and turned again to the law of the Lord.

As they did not repent the prophets' warning came true, and Sargon invaded and destroyed the Kingdom of Israel.

But Nahum brings comfort, for he tells the suffering Kingdoms of Judah and Israel that the Kings of Assyria shall so disappear that in the years to come the very place where they dwelt shall be forgotten, while Judah shall keep the Lord's feasts for ever. (Nahum i. 15.)

The Bible tells of many of God's acts which seem very wonderful to us. We call these acts 'miracles,' because we cannot explain them, nor how they happened.

Now the writings of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the rest of the prophets are also miracles, for although these men wrote at widely different times, and hundreds of years before the birth of Christ, yet their books all speak of Him. The light of God's Spirit shone into their hearts so that they foresaw and foretold the coming of the Saviour King.

Terrible troubles would overwhelm the Jews; but, even though the wall of Jerusalem should be broken down, the city laid waste, and the inhabitants led away captive, God's words were sure. He would visit His people at last. He would redeem them from their sins.

The troubles came, the prophets' eyes streamed with tears, and their hearts were torn with grief as they saw their land wasted by the heathen. Yet they did not despair. The dark night of sorrow would wear away at last, God's people should be brought back, Jerusalem rebuilt; her King would come, the Sun of Righteousness arise, 'And His name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The Mighty God, The Everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace.' (Isaiah ix. 6.)

[1] A companion volume to this book.

t last the full punishment for their many sins fell upon God's chosen people.

The words of warning written in the fifth book of Moses had told them plainly that if they turned aside and worshipped the wicked idol-gods of Canaan, the Lord would take their country from them and drive them out into strange lands.

Yet again and again they had yielded to temptation. And now the day of reckoning had come.

Nebuchadnezzar, the great king of Babylon, sent his armies into the Holy Land. No nation at this time could resist Nebuchadnezzar; even the fierce Assyrians had to bow before him, for he was one of the most powerful kings the world has ever seen.

Yet even Nebuchadnezzar was but an instrument in the hands of God, as Daniel recognized when he said: 'Thou, O king, art a king of kings: for the God of Heaven hath given thee a kingdom, power, and strength, and glory.' (Daniel ii. 37.)

This thought had been Daniel's comfort and stay, though he had been carried into the great heathen land far from Jerusalem, his beloved and holy city. But to those Jews who had no trust in God to uphold them, the sorrow was almost greater than they could bear.

For Nebuchadnezzar broke down the wall of Jerusalem, and led many thousands of her people away to be his slaves in Babylon.

'We have taken their treasure of gold and silver; we have laid their city wall in ruins; their Temple is bare and deserted; their gardens of lilies and spices are choked with weeds; their fields are unsown; their vineyards untended; the best men and women of the land are serving us in Babylon. Now, at last, there is an end of this proud Jewish nation, for all that they most valued is in our hands.'

So said the heathen Babylonians, mocking the poor captives. How little they dreamt that the Jews' most precious possession was with them still!

More valued than jewels or gold, sweeter than the milk and honey of their own land, was the Book of the Law—the Book which told them all they knew of God.

Indeed, not until the people were forced to live in a heathen city did they really learn to understand how great a treasure their nation possessed in the written words of God.

But in Babylon, with its huge heathen temples blazing with jewels and gold, its scores of cunning idol-priests, who deceived the people by pretending to tell fortunes and make charms, and its countless images, here, at last, God's chosen people began to see the greatness of the gift with which the Lord had blessed them, when He gave them the words which have now become the first books of our Bible.

Nebuchadnezzar might break down the wall of their city, he could not break down the spiritual wall which God Himself had built round His people. Scattered through many lands, forced to serve heathen masters as they were, the Book of God's Law was a living gift which bound the Jewish people together.

As we have seen, the Psalms were written by different writers, and one of the later Psalms, the 137th, gives us a vivid picture of those sad days: 'By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.' (Verse 1.)

Babylon was famous for its great rivers; and the poor captives watched the flowing water, and the great wind-swept beds of reeds and giant rushes. 'We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof.' (Verse 2.)

But their Babylonian masters had heard of the sweet psalms of the Lord's people. 'Sing to us,' they said; 'sing us a merry song. Sing us one of the songs of Zion.' (Verse 3.)

'Sing to these cruel heathen who have wasted our country, and carried us away into slavery! Sing one of the holy songs of Israel, the songs which King David wrote, that they may laugh and mock at us! How shall we sing the Lord's song in a strange land?' (Verse 4.)

No, they could not sing; their hearts were breaking with grief. Never, never could they forget the Holy City. Ruined, desolate as it lay, Jerusalem was still to them the place most loved in all the world.

And yet, even in far-off heathen Babylon the Lord called men to add to His Book.

The Book of Daniel has troubled many people greatly. It was not history at all, some critics said, but a mere collection of myths and legends. But year by year, as fresh discoveries are made, we see ever more clearly that it would have been better to trust the old Bible words after all.

'There never was a ruler over Babylon named Belshazzar' so these people said; 'the last Babylonian king was Nabonides.' A few years ago, however, Belshazzar's name was found on an old cuneiform tablet. Nabonides had been crowned king, but he seldom took any part in the affairs of the empire. All that he left to his eldest son, Belshazzar, who seems to have acted as king in his father's stead.

Almost daily further discoveries are being made, all proving the accuracy of Daniel's writings. What is probably the floor of the very dining-hall in which the hand-writing appeared has recently been uncovered.

Cyrus,[1] of whom Ezra speaks in the first chapter of his book, was a very different king from Nebuchadnezzar.

Nebuchadnezzar loved to pull down and destroy nations; but the great wish of Cyrus was to build up and restore. The cuneiform writings of the old Babylonian and Assyrian kings consist mostly of long lists of the nations they led away into slavery and the towns they burnt with fire; but the inscriptions made by Cyrus, the Persian king, speak of the people he sent back to their homes. 'All their people I collected, and restored their habitations.'[2] And among these people, as the Bible tells us, were the Jews of Jerusalem.

Many and great were the difficulties before them; but led, during the reign of Artaxerxes, by Ezra and Nehemiah, they faced their troubles bravely, until at last the wall of Jerusalem was rebuilt, and the city restored to something of its old beauty.

What a time of joy and triumph! Hardly could the Jews believe that they were in their own dear city once again. Psalm cxxvi. describes this wonderful day.

'When the Lord turned again the captivity of Zion, we were like them that dream. Then was our mouth filled with laughter, and our tongue with singing: then said they among the heathen, The Lord hath done great things for them.' (Verses 1, 2.)

'We have sinned against the Lord, we have been untrue to our promises; but never again will we neglect His Book, nor forget His Law.'

'And all the people gathered themselves together as one man...; and they spake unto Ezra the scribe to bring the Book of the Law of Moses, which the Lord had commanded to Israel.' (Nehemiah viii. 1.)

A solemn day that was, as we read in the Book of Nehemiah, a day of real returning to the Lord. Picture them standing there, those men and women and little children of Jerusalem; their faces would be worn with toil and hardship.

On a raised platform of wood stood Ezra ready with the rolls of the Books of the Law, and beside him were the interpreters.

For the people had been so long in a strange land that scarcely any of them could speak Hebrew; that is, the old Hebrew language in which King David wrote. If the Law of God was to be impressed afresh on the nation's heart that day, the scribes, the writers and the teachers must translate it into the language of their heathen conquerors.

'So they read in the Book of the Law of God distinctly, and gave the sense, and caused them to understand the reading.' (Nehemiah viii. 8.)

Since those days of Ezra, the Bible has been translated into nearly every known language. It is most interesting, therefore, to read in the Bible itself about what was most likely the very first translation of all—and this not a written translation, remember.

Now when the people heard the words of God's Book they were very sad; for now at last they understood how deeply they had sinned against Him.

They had been proud of their Bible, and had rightly felt it to be a great treasure; but now they saw that the words of the Bible must be shown forth in the lives of those who believe. To honour God's Book is not enough; we must obey it.

The Jewish people did not again learn to speak the old language of their nation. Yet all the copies of the Books of the Law, and the Books of the Prophets, the Psalms, and those writings which tell of the history of the Lord's people—that is, the whole of the Old Testament—were still written in the ancient tongue.

So it came to pass, after a while, that the Bible could only be read by the learned people; for the words in which the Law of God was given had become a 'dead language'—that is, a language that had ceased to be used in daily life at all.

Before the death of Ezra and Nehemiah, or else very soon after, the scribes of Jerusalem—that is, the writers and teachers—began to devote themselves almost entirely to the studying and copying of the Bible.

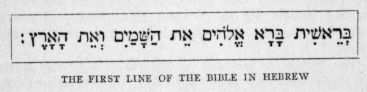

A young lad of those days who became a pupil in the School of the Scribes at Jerusalem would have to begin by learning the Old Testament almost by heart. To read an old Hebrew writing correctly was almost impossible, unless you had heard it read two or three times, and knew pretty well what was coming. For the ancient Hebrew alphabet consisted entirely of consonants; there were actually no vowels!

The little dots you see in the specimen of Hebrew given on this page are called 'vowel-points,' and are a guide to the sound of the word; but in the old, old days of which we are speaking, these dots had not been invented. The reader had nothing but consonants before him, and was obliged to guess the rest.

Just think of it! Suppose we followed this rule in English, and you came to the word, 'TP,' you would be puzzled indeed to know whether tap, tip, or top was meant!

But the Jewish scribes had wonderful memories. A teacher would read a long passage from the Psalms to his pupil, and very soon the lad would be able to repeat the whole correctly, the consonant words just refreshing his memory.

This would not always be as difficult as you might suppose. For instance, you can read this easily enough:

'TH LRD S M SHPHRD SHLL NT WNT.'

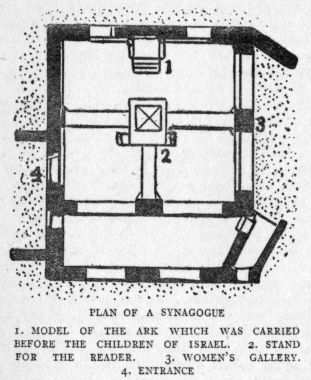

Indeed, to this day the Hebrew of the sacred Books in the Jewish Synagogues is all written without vowel-points.

At this time it was that the Jews became really the 'People of the Book,' and that a special society was formed to guard and copy the Bible.

How wonderfully this work was done! Never have the words of any other book been so lovingly cared for.

We have called the Bible the oldest Book in the world; we have seen that it tells about nations and people who were almost forgotten before the days of Abraham. It seems strange, therefore, that the most ancient copy of the Old Testament Scriptures, written in Hebrew and in the possession of the Jews to-day, carries us back only to the time of our Saxon kings.[3]

This is because the Jews' custom is reverently to destroy every copy of the Books of the Old Testament—that is, of their Bible—as soon as it becomes worn with use, or blurred with the kisses of its readers.

'This is a living Book,' they say; 'it should look new. God's Word can never grow old.'

So, year by year, they make new copies directly the old are worn out, and this they have done for long ages. And so careful have they been in making the copies, that although all was written by hand, there has practically been no alteration in the words for more than two thousand years. God had indeed well chosen the guardians of His Book.

Let us try to picture to ourselves a young scribe of those old, old days, with his dark hair and big, serious eyes, and dressed in his white robe.

He has been very patient and industrious for many months past, working early and late; now, at last, he is to be allowed to copy one of the sacred books.

'My son,' his old teacher has said, 'take heed how thou doest thy work; drop not nor add one letter, lest thou becomest the destruction of the world.'

'Oh, may the Lord keep my attention fixed, may He hold my hand that it shake not!'

So, with a prayer on his lips, the young scribe begins his work.

And it is through such patient, careful work as his that the older part of our Bible has come down to us from the half-forgotten ages of the past.

[1] Cyrus became King of Persia 546 B.C., conquered Babylon 538, died 528 B.C.

[2] Cuneiform writing made by order of Cyrus.

[3] The Codex Babylonicus, the earliest known Jewish manuscript, dates from the year A.D. 916.

ut troubled times came again to Jerusalem. The great empires of Babylon and Assyria had passed away for ever, exactly as the prophets of Israel had foretold; but new powers had arisen in the world, and the great nations fought together so constantly that all the smaller countries, and with them the Kingdom of Judah, changed hands very often.

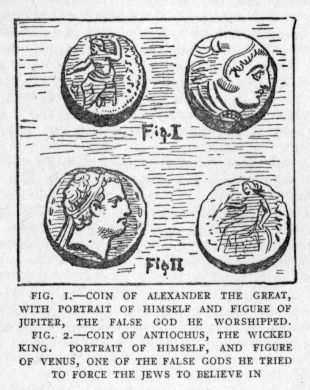

At last Alexander the Great managed to make himself master of all the countries of the then-known world. Alexander was an even greater conqueror than Nebuchadnezzar had been. He did not treat the Jews unkindly; he neither interfered with their religion nor took treasure from their temple.

Yet while Alexander did God's people no outward injury, his influence and example led them astray.

For Alexander was a Greek, and the Greeks, although at this time the cleverest people in the whole world, were a heathen nation, and as such did many foolish and wicked things. Alexander himself offered sacrifice to Venus, Jupiter, and Bacchus (the pretended god of wine and strong drink[1]), and to many other gods of man's invention.

Never again would God's chosen people willingly worship false gods; their troubles had cured them once for all of that sin.

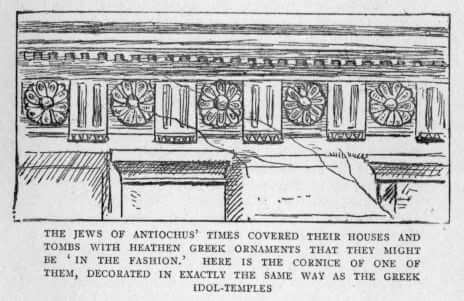

But although they knew the Greek religion to be untrue, they began greatly to admire the Greeks themselves, and to take their opinion about many things.

'Who can build like these Greeks?' they will have said. 'Who can carve such beautiful statues, or paint such beautiful pictures? Every one knows that their poetry is the finest in the world, and that their books are the wisest and pleasantest to read; and then, how well they train their young people! The lads of Greece are the strongest wrestlers and the swiftest runners in the world!'

All this was quite true; but the Jews forgot that mere cleverness does not make a man or woman good, and that the fear of God is the beginning of all true wisdom. Many people forget this even to-day.

So the Jews began to give their children Greek names, and to send them to Greek schools, and, what was worse, they put Greek books into their hands instead of the Bible.

Slowly but surely this unholy 'leaven' entered the people's life, and influenced their thoughts. But, in spite of all, many Jewish men and women remained faithful to God; they kept His laws, and read in His Book daily, looking always for the coming Saviour, the Messiah, who would rule and redeem His people.

As the years passed the fashion for Greek ideas and ways grew stronger in Jerusalem, until at last even the High Priest himself[2] began to encourage the people to neglect the services and sacrifices of the Temple, that they might go to heathen sports and games.

The Greeks were very fond of foot-races and wrestling-matches, and they held large athletic meetings two or three times a year; but no one who believed in God should have gone near those meetings, for the Grecian games were always held in honour of some heathen god or goddess.

When Alexander died he left his vast empire to be divided among his generals, just as Napoleon did centuries later with his conquests. The descendant of one of these generals was named Antiochus, and he began to reign over Syria, which included the country of Judah, a hundred and seventy years before the birth of Christ. He was known as Antiochus IV, and was a selfish and cruel ruler.

Although indifferent to his own heathen religion, he set himself to destroy all other forms of faith. 'I am king; all my subjects shall think as I do,' he said. He was told that the Jews believed in only one God, but he cried with a scornful laugh, 'Yes, but I will soon alter that!'

Before this there had been trouble between Antiochus and the people of Jerusalem, and he thought to himself, 'I must break down their old ideas and force them to disobey the laws of Moses, as they call them; above all, I must utterly destroy their Book. The Book of their Law once gone, they will be easy enough to manage.'

So he sent one of his generals to Jerusalem, and bade him take an army of soldiers and 'speak peaceable words unto them; but all this was deceit.'[3]

The orders of Antiochus were obeyed; the Jews suspected nothing, and the soldiers kept quiet until the Sabbath day.

But while the Jews were at prayer, and unable to defend themselves, the treacherous Greeks 'fell suddenly upon the city, and smote it very sore, and destroyed much people of Israel.' Then these wicked men built a strong castle on the hill of Zion, so overlooking the entrance to the Temple that no one could come in or go out without the knowledge and consent of the governor of the castle.

But this was only the beginning of sorrows. Soon the dreadful orders of the heathen king were cried through the streets of Jerusalem:

'It is the will of Antiochus the king that all the people throughout his whole empire shall worship the same gods as himself, and shall declare that his religion alone is true. Death to all those who disobey.'

The Jews looked at one another in utter dismay, for they knew well that Antiochus had power to keep his word.

'No more burnt offerings may be made to the God of the Jews in the Temple. I forbid the keeping of the Sabbath. The Jews' law declares the flesh of swine to be unclean. I command that on the altar of the Jewish God, in His Temple at Jerusalem, a sow be offered in honour of my god Jupiter. The Priests themselves shall be forced to eat of it.

'As for the Books of their Law, destroy them utterly; let not a word remain in the whole land. Publish this order against the Book; and if, after my will has been declared, any man is found to have a copy in his possession, let him be put to death.'

Horrible as it seems, all these wicked commands were carried out. A sow was slaughtered on the altar, and an image of Jupiter set up in God's Holy Temple. More cruel than all, the Book of the Law was torn and trodden underfoot.

Throughout Jerusalem and all the cities of Palestine bands of soldiers went everywhere searching for copies of the Scriptures. Torn to fragments, burnt with fire, often, alas! drenched with the life-blood of those who loved them, now, indeed, the Books of the Bible were in terrible danger, for the most powerful king of the fierce heathen world was fighting directly against them!

'O God, the heathen are come into Thine inheritance; Thy holy Temple have they defiled; they have laid Jerusalem on heaps.... The blood of Thy servants have they shed like water round about Jerusalem; and there was none to bury them.' (Psalm lxxix.)

So the cry went up from those faithful hearts who still dared to serve the true God.

The altar—the Temple itself—was now defiled, made 'unclean'; the Book of the Law had been torn to fragments; but His people could still cry to the Lord, and He heard.

They did not obey the wicked heathen king; and the stories of their courage thrill our hearts as we read them, for they show us what those saints of old suffered rather than deny their God.

'They were stoned, they were sawn asunder, were tempted, were slain with the sword: they wandered about in sheepskins and goatskins; being destitute, afflicted, tormented; (of whom the world was not worthy).' (Hebrews xi. 37, 38.)

It was of these times especially that the writer of Hebrews was thinking when he penned those words.

Seven young men, the sons of one woman, were with their mother brought before the king's officer—or, as some say, before the king himself—for refusing to break the laws of God.

They were cruelly beaten, but one of them cried:

'What wouldst thou ask of us? We are ready to die, rather than to transgress the laws of our fathers!'

The torturers thereupon seized the brave fellow, and so cruelly tormented him that he died, his mother and brothers being forced to look on.

But though their faces grew pale as death, and they quivered with anguish to see their loved one suffer, they gazed steadfastly at each other.

'The Lord looketh upon us, the Lord God hath comfort in us,' they said.

Then the second son was taken, and before he died he cried with a loud voice, looking his heathen judge full in the face:

'Thou, like a fury, takest us out of this present life, but the King of the world shall raise us up, who have died for His laws, unto life everlasting!'

But when it came to the turn of the youngest son even the heathen judge was anxious to spare him, and he promised the lad honour and great riches if he would but turn from his faith.

But the youth stepped out before them all, his boyish face as brave as a man's and his boyish voice as steady.

'Whom wait ye for?' he asked. 'I will obey the Commandments of the Law that was given unto our fathers by Moses; but thou shalt not escape the hands of God.

'We suffer for our sins, but our pain is short. See, I offer up my body and life for the Laws of my fathers, beseeching God to be merciful to my nation, and that thou at last mayest confess that He alone is God!'

Last of all, after her sons, the mother died as well.[4]

But the saints of God did not die in vain; their victories over pain and death fired the hearts that had grown so cold, and awakened the careless into active life. Those who had forsaken the religion of their fathers returned by hundreds to God, confessing their sins, and pleading for pardon.

So the very fierceness of the trial proved a blessing, and the days of torture were followed by a revival of faith in God, and devotion to His service.

Now there was an old priest named Mattathias who, with his four sons, had never listened to the cunning temptations of the heathen Greeks. All his life he had served God with his whole heart, and had brought up his sons to follow in his steps. When Mattathias and his sons heard what was being done at Jerusalem, they clothed themselves in sackcloth and wept, praying, and fasting continually, beseeching God to forgive His people, and to put away their sins.

In a little while the king's officers came to the heathen altar at Modin, the town where the old priest lived.

'Sacrifice to Jupiter, our master's god!' they said. 'Sacrifice, as all Jews shall be forced to do, or die!'

But the old man looked the Greek straight in the face. 'Though all the nations in the world obey the king, yet will I and my sons walk in the covenant of our fathers. God forbid that we should forsake His Law.'

As he spoke a backsliding Jew stepped up to the altar to sacrifice. The old priest's eyes flashed fire, and in an instant he had struck him down, and the Greek officer with him.

Quivering with indignation Mattathias then turned to the startled people: 'Whosoever loves God, let him follow me!'

And he turned and fled swiftly through the streets of the city.

Many followed him at once. Others joined him later in the strong camp he formed in the mountains, until at last he was at the head of an army.

Wonderful it is to read how, little by little, this army of God's people drove the heathen from the cities of Judah; how they overturned the heathen altars, and cast down the images of the false gods; and how, at last, they came to Jerusalem, cleansed the Temple, and purified the golden altar from the stains of heathen sacrifices.

Then, tenderly and reverently, they gathered together all that was left of the copies of their Scriptures, weeping as they saw the poor fragments, blackened with fire, stained with blood, and scrawled all over with the horrible figures of heathen gods.

As to-day we read in the clean white pages of our Bible, let us remember this scene and of the time when those torn and blood-stained fragments were all that remained to the world.

But, thank God, when all the pieces had been collected together, there was plenty of material from which to make fresh copies; and no sooner had peace been restored to the city than the scribes set to work, with eager, loving care.

The Book had become doubly precious now! Its written words were indeed sacred, for the blood of martyrs had fallen upon them, and men and women, and little children, too, had chosen to die by hundreds rather than to deny them.

[1] With all his cleverness, Alexander, while still quite young, drank himself to death.

[2] In the days of Joshua, who bought the office of High Priest under the reign of Antiochus, so many priests took part in the games that the regularity of the Temple services suffered.

[3] From 'Maccabees,' an old Jewish history, which is sometimes bound up with our Bible.

[4] This is taken from 'Maccabees.'

y the blue waters of the Mediterranean Sea, on the coast of Egypt, lies Alexandria, a busy and prosperous city of to-day.

You remember the great conqueror, Alexander, and how nation after nation had been forced to submit to him, until all the then-known world owned him for its emperor? He built this city, and called it after his own name.

About a hundred years before the days of Antiochus (of whom we read in our last chapter) a company of Jews were living in Alexandria, then a rich and beautiful city, with its stately palaces and temples of white marble, its beautiful gardens, and groves of graceful palm-trees.

After the death of Alexander, the Greek kings of Egypt delighted to live in the new city, and in the old Greek books we can yet read of the splendid processions and festivals held in its streets year by year.

At this time Alexandria drew all the merchants of the world to her markets; and her harbour was constantly filled with ships laden with silver, amber, and copper; while caravans were arriving daily, bringing jewels and rich silks from China, India, and the cities of the far East.

The Jews of Alexandria were not treated as foreigners, but as good subjects and citizens, by the Greek rulers of Egypt, and therefore as the years passed they grew rich and honoured in their beautiful home. Their children, however, seldom if ever heard Hebrew spoken; for all the Jews of Alexandria, for convenience' sake, spoke Greek like their neighbours.

But, although these Jews lived in a heathen city where they read nothing but Greek books, and heard Greek spoken all day long, they did not forget their God. They longed as earnestly as ever to hear about Him, and to read in His Book; but what was to be done? Only a few of the elder Jews could read Hebrew, and their children could not understand one word of the language. Must the little ones, therefore, grow up in ignorance of the Word of God?

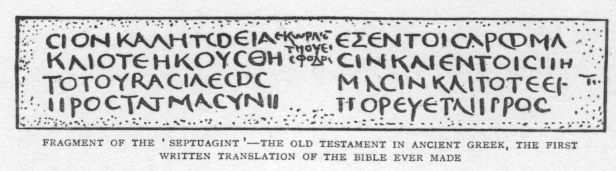

This was impossible. Here in the heathen city of Alexandria the Scriptures would be the only safeguard of Jewish boys and girls. 'If the language of our children is Greek, then the Bible must be translated into Greek, so that they all can understand it.' So said these Jewish parents.